Growing up in Detroit, I remember a time in junior high when a group of older boys came onto our playground looking for a fight, and to claim our grounds. They asked, “Who’s the toughest kid here?” Someone pointed to a boy sitting quietly under a tree. The high schoolers sent word: We’re here to kick your ass.

Being nonviolent and a bridger does not mean that one is not willing to fight.

The boy didn’t move. When the message was delivered, he simply said, “Tell them, if you want to kick an ass, you have to bring an ass.”

That experience has stayed with me. It was a reminder that even when confronted, even when outnumbered, you don’t surrender your ground without making it clear that those who come after you will know they’ve been in a fight.

Some may find my telling this story strange. People know me as a bridger and someone who deeply believes in nonviolence. Those observations are accurate. Yet, I share this story because this is part of my history, and to make the point that being nonviolent and a bridger does not mean that one is not willing to fight.

Today, as authoritarian movements gain ground across the world and here at home, that lesson feels urgent. When powerful forces seek to shrink the scope of democratic practice, to scapegoat the vulnerable, and to undermine belonging itself, our institutions and communities must remember that to defend what matters most, you have to show up. You cannot fold quietly and hope to be spared.

The story of the United States has always been a struggle over who gets counted in the “we.”

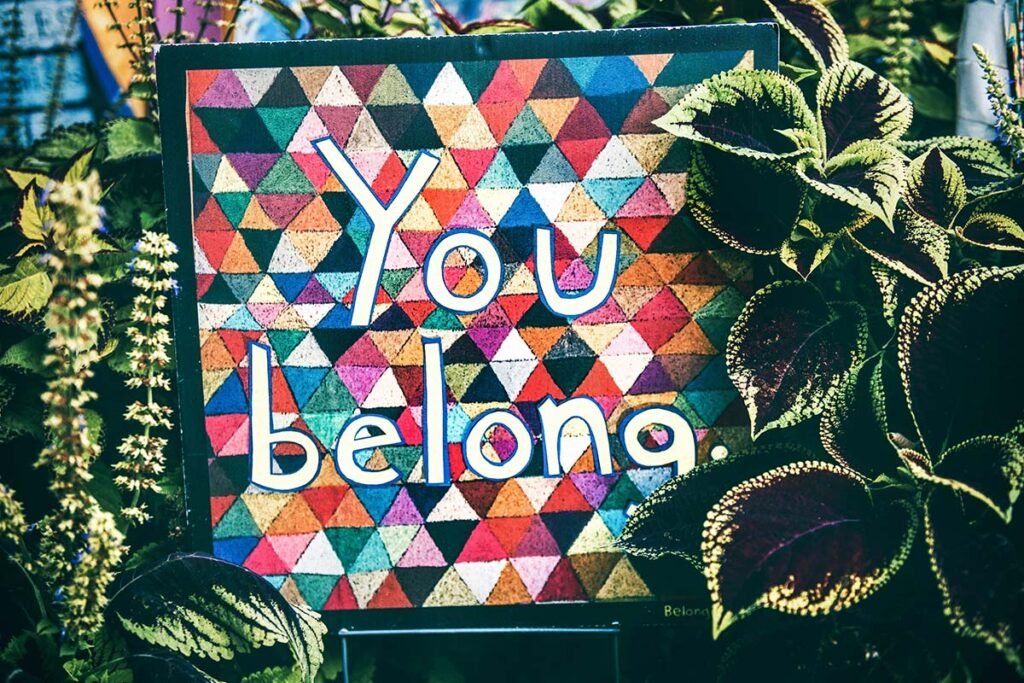

And yet, the deeper lesson I learned during that moment on the playground isn’t just about defiance: It’s about belonging.

That boy knew he wasn’t standing alone. He was part of a “we,” and that gave him strength. Standing up to the bullies on that playground increased a sense of belonging for all of us. The fight against authoritarianism is, at its core, a fight over who belongs—and whether we can build a civic “we” expansive enough to resist division and fear.

Civic Life and the Struggle over Who Belongs

The story of the United States has always been a struggle over who gets counted in the “we.” The Declaration of Independence spoke of equality, but it excluded enslaved Africans, Native peoples, the unpropertied, and women. Civic life was imagined as people gathering in schools, churches, and public squares—but only some were allowed to participate fully.

At every turn, people have fought to widen the circle—to stand up for belonging and each other. Abolitionists, suffragists, civil rights leaders, immigrants, laborers, LGBTQ+ communities—each demanded not only rights but recognition and a say. They demanded belonging, and they fought for belonging by bridging and embracing nonviolence. As we stand up to support belonging, it is not enough to just stand up for “our people,” it must be done for all people, and our planet.

But every expansion of belonging has been met with pushback. Each new voice added to the “we” has been greeted by some who used fear to shrink it again. That contest is the heartbeat of our civic history and beyond.

In my book Belonging Without Othering, I assert that belonging is not simply about letting more people into existing structures. It means openness to transforming the structures and cultures themselves so that all can participate and thrive.

Belonging is not conditional or transactional. It is embracing the common humanity that each and every one of us share and express—even those we struggle against.

This belonging without othering may not reflect our current reality, but it does reflect our necessary life journey. Civic engagement is not just about voting or attending a town hall. It is about belonging—about being recognized as part of the community whose voice matters and whose dignity and humanity are nonnegotiable.

Belonging does not erase difference. It does not mean uniformity. It means a society where differences are not grounds for exclusion, but opportunities for connection.

And bridging is the practice that helps make belonging real.

As I write in The Power of Bridging, bridging is not about pretending our conflicts do not exist. It is about building enough trust and connection to hold those conflicts without dehumanizing one another. Bridging says: We are linked, and our futures are tied together.

When we bridge, we widen our circle of human concern. When we refuse to bridge, we retreat into smaller and smaller groups, in constant conflict, which leaves our civic life fractured and vulnerable. A limited “we” can never sustain real peace.

A Different Kind of Threat

For decades, US politics involved debates about interpretation and implementation of core values: How much should the government provide, how much should remain private, what does equality mean and require? There was often disagreement, but there was significant consensus on core concepts.

That is no longer the case.

Today, we face something different. An authoritarian movement fueled by fascism, backed by billionaires, and amplified by powerful media is not simply arguing about the meaning of our core values, it is rejecting them—or only using them when convenient.

This includes challenging the very premise of belonging. Advocates of authoritarianism insist that only some people count, that only some people deserve dignity, that loyalty is owed to a leader or a faction rather than to shared values or even codified rights such as equality and due process.

The strategy is familiar—target the most vulnerable, vilify them, and use resentment to consolidate power. Today, trans youth are under relentless attack. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are framed as threats—a threat to supposed ethnic and national purity. Immigrants are scapegoated as dangers rather than neighbors.

Political leaders today stoke resentment among working-class White people, while vilifying and othering those who aren’t White. The goal is to shrink the circle of belonging and make cruelty ordinary and accepted in service of a mean nationalism and unshared wealth and power.

This authoritarian fascist strategy isn’t just targeting people. It is tearing down and undermining institutions that are critical parts of “we the civic.”

Belonging cannot be a secondary concern, defended only when convenient. It must be the core.

Universities, hospitals, nonprofits, law firms, courts, even houses of worship are forced into what some have compared to the “trolley problem”: Either you accept the condition of excluding the targeted group, or you lose all your funding, harming everyone you serve. And if you choose the latter, you also become labeled part of the disloyal “other.”

This authoritarian move does not aim to save the many. It is not out of care for anyone that coercive arrangements like these “trolley problems” are created. The goal is to break the will of institutions, to make them choose survival over their values, and to erode democratic practices.

Too often, institutions fold. They tell themselves that concessions will buy time. But history shows the opposite. In Germany as early as 1933, universities, orchestras, and other cultural and civic institutions thought they could protect themselves by making compromises—dismissing Jewish faculty, canceling certain works, rushing to show adherence to nationalist edicts. In doing so, they sought survival, but they destroyed their own integrity. They lost their identities by abandoning their independence, values, and belonging.

The lesson is clear: An institution that abandons belonging has already lost, even if its doors remain open.

A university that silences marginalized voices is no longer a university. A hospital that refuses to treat vulnerable patients is no longer a hospital. A nonprofit that compromises its mission to avoid controversy is no longer a force for the common good.

Belonging cannot be a secondary concern, defended only when convenient. It must be the core. Without it, our civic world collapses into competing factions. And people are disposed of with impunity.

Courage, Bridging, and the Work Ahead

So, what is required of us now? Courage, yes. But that courage must be rooted in belonging without othering, and the practice of bridging.

We are at a precipice. Earlier generations were told that the threats they faced were too powerful, the risks too great, the divisions too deep. And yet they built bridges. They widened their belonging. They left us examples of courage that still inspire.

Now it is our turn.

The question is not whether we will survive as institutions or as individuals. The question is whether we will expand our belonging. Because without belonging, survival alone is meaningless.

Fortunately, there is reason for hope. Across the country, millions of people are speaking out. Communities are documenting abuses, organizing networks, and demanding recognition. This year has seen some of the largest single-day protests in our country’s history, and boycotts large enough to shock major companies. Polls show that many of the actions that mainstream media describe as “unprecedented” are also overwhelmingly unpopular.

The civic spirit is alive.

Many civic institutions, universities, law firms, and foundations are stepping up, forging collaborations and increasing their support. But let’s be clear: It’s nowhere near enough. The threats we face are escalating faster than our responses. If institutions do not act with greater courage and scale, we risk losing the very ground we stand on.

At the institute I direct, our Bridging for Democracy project seeks to connect residents, organizers, and community leaders across political, racial, and geographic divides to practice bridging in real time. Participating civic organizations have listening-centered conversations with people that they previously believed fell outside their “we.” Immigrant rights advocates canvass communities that have opposed migrant resettlement programs. Urban-based organizers take listening tours in suburban Milwaukee and rural Nevada. Parishioners from the political right and left discuss their personal stories of fear and hope in the meeting rooms of their church basements.

In these spaces, divides prove to be paper thin.

When people come together to share their stories, caricatures of the “other” tend to evaporate. These conversations do not erase differences, but they foster recognition, respect, and rehumanization.

Another example from our Institute is the Unconditional Belonging initiative which insists that no person or group’s inclusion should be contingent upon them accepting lesser rights, dignity, or say in our shared future. Co-created with community partners in Anaheim, CA, the initiative is applied across struggles for housing justice, stronger community voice in schools, civic engagement, and more. Grassroots community members describe feeling more respected, less subject to condescension or judgment, and more able to speak as their whole selves when they advocate for their communities through the language of unconditional belonging.

There is, of course, so much more that can be done to put bridging and belonging into practice. And we need fellow civic institutions with resources—universities, foundations, labor unions, nonprofits—to stand firmly on these values if we are to meet this perilous moment. They must be willing to risk short-term losses to defend the long-term value of their institutional missions, and of belonging. They must insist that threats and retaliation will not deter them.

As that boy on the Detroit playground taught me: If someone wants to bring a fight, you must make them know they got a fight.