When democracy is under attack, what can people do? “Stand up, fight back!” goes the street chant. But is that enough?

Yes, resisting attacks is important. But defending the status quo alone is a losing strategy when most people don’t like the current system of government. Most people in the United States, across nearly all demographic groups and ideologies, say that the nation’s government does not work for them, according to a Times/Siena College poll. Worldwide, the Pew Research Center found in 2021 that most people in electoral democracies think “their political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed.”

These people are not wrong. A decade ago, political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page concluded that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on US government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.” It’s no wonder people want change!

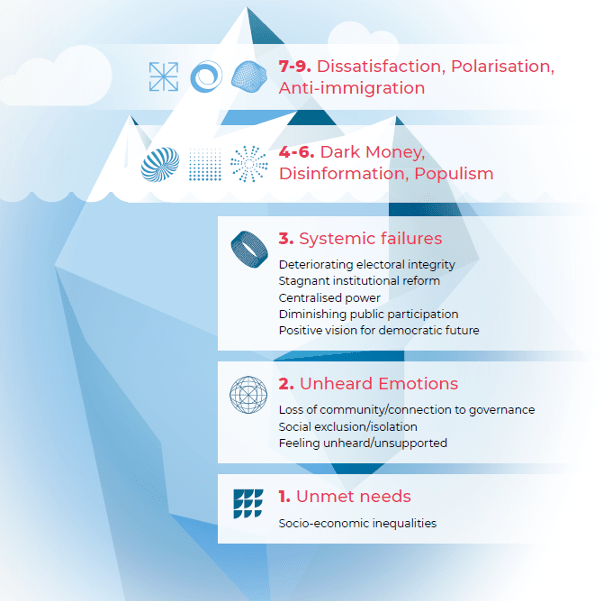

While rising polarization and anti-immigrant sentiment are highly visible, they are symptoms of democratic backsliding rather than causes.

Making systemic changes to democracy isn’t easy. Too often, we look for one magical solution that will change everything. Democracy advocates around the world have identified more promising approaches. Based on this work, I suggest that we focus our attention on three emerging strategies for democracy renewal:

- Roots: Address the hidden root causes that are driving democratic backsliding.

- Horizons: Envision and start building the desired future of democracy.

- Ecosystems: Build bridges, infrastructure, and narratives to connect existing efforts.

Unfortunately, only a sliver of democracy funding and work currently aligns with all of these strategies. In the United States most funding focuses on maintaining and defending existing systems of electoral democracy—it’s time to move beyond defense and put these alternative strategies into practice.

How to Address the Root Causes

Democratic practices of governance are in crisis, and we need to first understand the underlying ailments if we want to fix them. Otherwise, we may end up just treating the symptoms.

The Democracy Iceberg framework developed by Philea, the Philanthropy Europe Association, helps distinguish the causes of backsliding from the symptoms. It maps root causes of people’s frustration, catalysts that amplify this discontent, and the resulting visible symptoms. While rising polarization and anti-immigrant sentiment are highly visible, they are symptoms of democratic backsliding rather than causes.

According to Philea, unmet needs, unheard emotions, and systemic failures are the root causes driving polarization and anti-immigrant sentiment. When people are struggling to pay their bills, feel that their voices aren’t being heard, and think that the system is broken, they are more susceptible to polarizing “us-versus-them” rhetoric and more inclined to blame others for their problems.

To alleviate the symptoms of democratic backsliding, advocates need to address the root causes by changing how democratic institutions work. This can be accomplished by:

- To respond to unmet needs, reshape policymaking for these needs. Campaigns and programs that increase people’s decision-making power over essential goods and services, such as housing and healthcare, show how democracy can meet people’s needs. This requires a mix of organizing, policymaking innovation, research, and communications to create a clear link between people’s democratic engagement and resulting material benefits. Of course, this kind of organizing means contesting for power and challenging powerful forces, such as private equity owners of housing and healthcare, that have stood in the way of giving people meaningful control in these areas.

- To address unheard emotions, develop spaces for social and emotional connection. Community dialogues, legislative theater, and artistic and cultural engagement invite people to express themselves emotionally and listen to their neighbors. This may involve bringing public voices into existing policymaking, setting up new spaces and programs, and researching how to make democracy resonate with people emotionally.

- To fix systemic failures, invite people to change the system. This can be done by expanding programs that help people participate in decision-making and fix bureaucratic inefficiencies. For example, citizens’ assemblies convene groups of randomly selected citizens to determine community priorities and develop solutions. Participatory budgeting invites residents to decide how to spend public funds. Participatory policymaking engages masses of people in shaping public policies. These innovations build trust and democratic muscle by making policymaking much more responsive to the public’s needs.

But reversing the current problems is only part of the puzzle—we also need better solutions for the future.

Envisioning Future Horizons

If the status quo is deeply flawed, how can we build meaningful and accountable democratic governance? Programs such as the Democracy Futures Project of PACE (Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement) are envisioning paths forward. This 18-month program aims to help 60 participating funders spot trends and think long-term about US democracy.

Of course, while the PACE program is directed at funders, a longer time horizon is vitally important for nonprofits and movement actors as well. PACE and others are using this future thinking to better understand what to keep from the current system, what emerging practices to explore, and what seeds of future change to support.

Emergent strategies that go beyond defending the status quo are required…such as citizens’ assemblies, participatory budgeting, and new digital participation tools.

The first lesson from future visioning is that, in general, democracy advocates currently focus on defending the “business as usual” system. This accounts for the vast majority of pro-democracy funding. And for nonprofits and movement groups that depend on philanthropy, the focus on short-term results often detracts from the long-term relationship building that supports stronger democratic infrastructure.

When describing the 2024 election, Harvard scholar-activist Marshall Ganz was scathing in his assessment:

There were a bunch of people with a lot of money giving money to community organizations to canvass. The donors’ item of value is how many doors you have knocked on….I know community organizations that are struggling with this. Because they want to be organizing. But all this money comes in and then they are running these mobilizing operations…because the sources of money want something that they can count.

Of course, some electoral work should be sustained, but emergent strategies that go beyond defending the status quo are required. Some of these are already visible, such as citizens’ assemblies, participatory budgeting, and new digital participation tools.

This isn’t enough, however. The more challenging task is to envision new democratic systems and processes that do not yet exist. This demands greater imagination and experimentation—trying new approaches that might have a higher risk of failure.

Gideon Lichfield, former editor in chief of Wired, offered a glimpse into what this might involve, with the future story of “Sandra.” In Lichfield’s imagined scenario, Sandra’s personal digital assistant points her to relevant neighborhood discussions and national legislation, directly feeds her input (alongside that of many others) to government representatives and participatory programs, and alerts her to the outcomes and next steps. Bits of this future are already possible today, but they need more nourishment, testing, and development to grow.

Focusing more on longer time horizons can provide enticing paths forward. But what concrete work helps us move along these paths? Ecosystem strategies from democracy practitioners are providing direction.

Building Connected Ecosystems

When democracy advocates and funders look to the future, they usually focus on innovation. What new and sexy practice can get us out of our malaise? Unfortunately, this is part of the problem. No single innovation will address the root causes of democratic backsliding on its own. Shifting from one innovation to another comes at the expense of long-term systemic change. The only solution is many solutions, connected together.

In the white paper From Waves to Ecosystems: The Next Stage of Democratic Innovation, I outline a path forward that focuses on lifting up emerging innovations of international democracy advocates. Often, activists have adopted a single-vector approach, such as advocating for deliberative democracy. Today, however, more advocates are seeking to weave together multiple democratic practices that might result in balanced democratic ecosystems.

What do democratic ecosystems look like in practice? There are many enlightening examples from around the world, from local strategies in Paris to the national level in Brazil.

In Paris, the city council launched a permanent Paris Citizens’ Assembly, citizens’ juries, and participatory budgeting, which coordinate their work to engage more people in democratic decision-making—and help the council better represent and serve its residents.

No single innovation will address the root causes of democratic backsliding on its own.…The only solution is many solutions, connected together.

In Brazil, the federal government has used National Public Policy Conferences (Conferências Nacionais) to engage millions of people in deciding key policies, and it coordinates a national digital platform, Brasil Participativo, to connect different participatory policymaking efforts.

What concrete work can turn democratic innovations into system change? A few approaches have been most promising:

- Connecting Practices: Advocates have combined or linked democratic practices and movements in three ways. First, by connecting different kinds of democratic processes, such as training political candidates to use participatory methods and integrating participatory budgeting and citizens’ assemblies. Second, by connecting democratic practices across geographic scales, such as the Global Citizens’ Assembly that links local and international assemblies. Third, by connecting democracy and issue-based movements, such as the EU’s Democracy for Transition Coalition that brings together democracy and environmental organizations to promote climate democracy.

- Sharing Infrastructure: Movements have set up common staffing and support for different democratic practices. Rather than focusing on separate campaigns for electoral reform, voter engagement, citizens’ assemblies, and participatory budgeting, funders and movements can nurture cross-cutting democracy coalitions, resources, and programs.

For example, the Open Government Partnership’s Multi-Stakeholder Forums unite diverse civil society groups and government officials to make open government reforms. This helps them understand the range of democratic practices, and how they can cut costs and increase impacts by sharing software, vendors, publicity, and other support. Likewise, the growing ecosystem of digital participation tools, such as those at People Powered, lets practitioners implement a wide range of democratic practices using a single platform.

- Framing Narratives: Researchers and advocates are developing shared language to communicate what democracy is and what it could be. Often, advocacy for democracy is technocratic—promoting rule changes, institutional reforms, and complex processes. This may motivate experts but not broader movements for change. Increasingly, advocates are recognizing that they need more compelling shared narratives to build support for systemic change.

The Metropolitan Group, for example, recently compiled 12 democracy narratives and 10 values that seek to advance democracy. The new Democracy Narratives Campaign, also at People Powered, is synthesizing this and other research to turn it into concrete messaging for engaging people in democratic practices and apply this new language through coordinated global communications, under the umbrella of the Global Democracy Coalition.

Toward New Strategies

Most democracy advocates and funders have unfortunately operated with short time horizons, resulting in approaches that run counter to the strategies outlined here. And advocates more often prioritize new innovations instead of connections among existing practices. These approaches are not working.

In contrast, anti-democratic movements have already been prioritizing the three strategies above, with immense success. They have fueled the root causes of democratic backsliding, invested in radically different long-term visions of governance, and built connective infrastructure at the national and global scale. While democracy advocates experiment with one-off pilot programs, anti-democracy advocates have built global movements with transformative 30-year time horizons.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The strategies described above can help address the root causes of backsliding, advance visions with longer time horizons, and build connected ecosystems. When democracy is under attack, advocates must do more than fight back. We need to build a better democracy.