In this county’s founding documents, people sure had an affinity for the word “we.” For example, the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence begins:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

While I am an unabashed believer in aspiration, it’s clear that this we was not meant to include me and Native peoples like me.

As evidence, one just has to jump just toward the end to see how the we of this emerging nation really felt about the original inhabitants of this continent, my ancestors, when the nation’s founders described them as “the Inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction, of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

American Indian assets [have] created…one of the world’s wealthiest economies, but at the expense of American Indian economic and human rights.

I often write about the work of First Nations Development Institute, where I serve as president and CEO. For 45 years now, we have been focused on and continue to fight for economic justice with, by, and for Native peoples. This, “with, by, and for” Indian Country is terribly important because that has hardly ever been the practice.

Here at First Nations, we stand by the aspiration that control of one’s economic destiny applies to all people equally, and that sharp vigilance and timely intervention can upend centuries of American Native peoples’ disenfranchisement that has kept them from controlling their own economies.

Voices of My Ancestors

At First Nations, we frequently share that the appropriated use of American Indian assets has created, in the United States, one of the world’s wealthiest economies, but at the expense of American Indian economic and human rights. In fact, Native Americans have routinely been deprived of the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that’s promised non-Native Americans. So, for me, the most important part of that sentence, so often quoted from the US Declaration of Independence, are not the words life, liberty, or happiness, but rather and—as in: Can we maintain our Native values and pursue our lives as we wish?

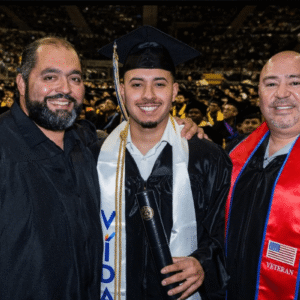

This focus comes to me due to three influential men in my life, all relatives—my grandfather, my father, and my brother.

Donald Roberts, my grandfather, was born in 1910, in the Alaska Territory, and while his every breath would be dictated by laws and government officials, he and his people (my people) would not gain the right to vote until 1924—almost 75 years after the Fifteenth Amendment gave formerly enslaved men the right to vote.

At age 11 he was sent off to boarding school in Oregon, travelling first by fishing boat from Klawock to Ketchikan, Alaska. From there, with his nine-year-old sister in tow, he boarded a steamship to Seattle. There he and my great aunt were required to find their way (unescorted, mind you) from the shipyards of Seattle to the train station, where they boarded a train to Chemawa Indian School in Chemawa, OR, near the state capital of Salem.

Google Maps indicates that is a three-day journey today. Imagine what it was then, and how many Native kids got lost along the way. At Chemawa, my grandfather was taught a menial trade because there was no room to be an Indian and something else, like a physician or attorney.

My father Peter Roberts, one week before he was to graduate from Ketchikan High School in 1959, had his English grade changed from an A to a B, keeping him from being class valedictorian—because in the minds of the school administrators, he could not be an Indian and a valedictorian.

My brother Joseph Roberts, unlike me, was athletic—perhaps the best pure jump shot shooter to come out of Ketchikan, but he was not chosen for the high school varsity team, because he was an Indian. There was little possibility to be Indian and a varsity basketball player.

But these three Native men and their sacrifices have allowed me to be Indian and.

Disrupting Myths

My life, and my recent life’s work, has been to promote economic opportunity, and along the way, change the perception of Native peoples. And, when I am honest with myself, I do this for two of the most important women in my life, my daughters Evan and Lauren.

Americans from very young have myths about Native Americans burned into their belief systems…many are not even aware of their existence.

But for this and to happen requires continually tearing down more than 500 years of mythology. And if you are curious to know more, First Nations a few years back published a seminal study on Native narrative, Reclaiming Native Truth: A Project to Dispel America’s Myths and Misconceptions.

There is a quote that always makes me think about the many false narratives that most Americans hold about Native peoples, this one by President John Kennedy, who, at a commencement address at Yale, said:

The great enemy of truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived, and dishonest—but the myth—persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.

These myths play out in so many ugly ways. Americans from very young have myths about Native Americans burned into their belief systems, so much so that many are not even aware of their existence.

Making the Invisible Visible

A great part of my work is not just the day-to-day stuff of raising money and running an organization—making grants and making economic development possible in some of the poorest “third world”–like environments here within the United States borders.

My work is to do all of this and, if I am lucky, on good days, I am allowed the opportunity and the privilege to help make Native peoples in this country—the invisible—visible.

Here at First Nations, we invest in the hopes and dreams of Native communities, and we invest in these communities’ own solutions.

Last year we, as an intermediary funder, regranted $17 million to Native-led institutions, putting us in the top 10 private foundations giving to Native-led organizations—but we did it without the well-heeled endowments of our peers in this group. Is it strange that a number that would put us at this level can inspire both pride in such an accomplishment and rage and disgust that the industry we have become part of continues to fail us? It reminds me of the James Baldwin quote, which I cite frequently:

It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you. It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you.

We have always been the Indians, but folks, under this presidential administration, the Indians are now you.

As Natives, we endure daily the smallest of slights. In most instances our invisibility keeps us from even getting mention at all, even something as simple as studies showing economic and health disparities.

In these studies, often underwritten by private philanthropy, we are not included. It would be nice if we could at least get an N/A. And while we know well that there is little disaggregated data on us, that shouldn’t mean that we are completely left off the charts, the graphs, and research reports.

We have always been the Indians, but folks, under this presidential administration, the Indians are now you.

We are constantly asking for the courtesy, that if data can’t be found, whether it’s enough data or timely data or statistically sound data—at least list us, followed by N/A for not applicable or not available. And I don’t mean N/A as in not allowed, like on the signs that were still on some shop doors in the town where I grew up: “No Dogs or Indians Allowed.”

And our inclusion cannot be as cultural objects. Can we just get a simple mention, not treatment as some dehumanized other?

Tim Wise may have said it best, when he noted:

Perhaps most importantly, we could begin by telling the truth about what was done to the indigenous of this land, rather than trying to paper over that truth, minimize the horror, and, once again, change the subject. You know the kind of people I’m speaking of: the ones who refuse to label the elimination of over ninety-five percent of the native peoples of the Americas “genocide.”

The Role of Philanthropy

The we who has been actively othering people in the country from the very beginning —our government and institutions—includes many private foundations today. Why stand up now?

Perhaps people in liberal institutions and foundations might suddenly feel the threat of becoming the wrong we?

Of course, every time First Nations and other BIPOC-led institutions share empirical data about the failure of philanthropy to fund institutions led by communities of color, the first thing people do is—well, it is not to look in the mirror—but to attack the data.

How do we know that Native and other Brown and Black people have not been included in the philanthropic we? Well, to quote former President Bill Clinton, “I always give a one-word answer: arithmetic.”

The Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University, in their recently released Communities of Color Index, reported that on average nonprofits in this country rely on government support for over 35 percent of their revenue. For nonprofits in communities of color in general, that number is nearly twice that amount, over 65 percent. For Native nonprofits, that number is 72 percent. These communities of color are, no surprise, the most impacted by the downsizing of federal programs and dollars.

In this same report, we learn that private philanthropy gives 2.9 percent of grants to communities of color, even as people of color comprise 44.3 percent of the nation’s population. Even this number overstates the giving: Grants serving specific communities of color total only 1.25 percent of grants (Asian American Pacific Islander: 0.17 percent, Native: 0.21 percent, Latine: 0.26 percent, Black: 0.61 percent). One might suggest that the private philanthropic industry should be among the institutions least in jeopardy of the current administration’s war on DEI, as the empirical evidence indicates there is negligible to no commitment by philanthropy for DEI funding practices.

Expanding the “We”

What can be done? I am not one to solely criticize without pointing to possible paths forward. Here’s one. As a simple action, private philanthropy could double down on its giving to Native-led and other community of color–led institutions. This simple action would begin a trend to equity. And it would only raise the payout of these private philanthropic institutions from 5 percent to 5.063 percent. To quote Bill Clinton: “Arithmetic.”

The we at our nation’s founding did not include us. There remains very little we in the way we are treated in today’s politics or by today’s philanthropic institutions.

If we at First Nations hope to be effective in over our next 45 years, we need to not only change the narrative of how Indians are made visible but also work on the way they are perceived—and allow them to enjoy the life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness promised by the nation’s Declaration of Independence.

So, when we’re asked to stand beside the sector at this moment, to be counted as part of the general we, we ask in turn to borrow the refrain from the Lone Ranger’s trusty, and much wiser, Native sidekick Tonto: “What you mean ‘we,’ Kemosabe?”