At first glance, it looked like a heartening story of factory jobs saved. The Illinois Development Finance Authority report featured a photo of a family-owned meatpacking company that had expanded with agency assistance.

But reading past the image, I saw that the company had been given tax-free financing to relocate from the South Side of Chicago, which is home to the state’s largest concentration of Black workers, to Schaumburg, a distant northwest suburb that in the mid-1980s was more than 90 percent White.

The episode jarred me: Was this how states do “economic development?” Just shuffling jobs around in a racially discriminatory way?

I’ve since uncovered five prevalent racist state economic development subsidy practices: geographic redlining, harm to public education, the deregulation of originally anti-poverty programs, the privileging of large corporations over small business, and the enrichment of elites through megadeals.

Below I outline how they function, and how community groups can most effectively respond.

Geographic Redlining

Twenty years after that jarring meatpacking story and after founding Good Jobs First, I looked back with a study that mapped 15 years of Illinois incentive deals (1990–2004) over the six-county Chicago metro area. Sure enough, the state was essentially redlining Chicago, especially its majority-Black South and West areas.

With 38 percent of the region’s population and 30 percent of its business establishments, Chicago was receiving only 15 percent of the subsidy dollars. State programs grossly favored the booming areas around O’Hare International Airport and wealthy suburbs in DuPage County.

We published several more subsidy-mapping studies as well. In places like Detroit, the Twin Cities, and Cleveland, these discriminatory patterns were sometimes even starker.

Using eight different equity metrics—including race, income, unemployment, mass layoffs, tax-base stress, and whether a workplace is accessible via public transit—we found that economic development programs are a form of “reverse Robin Hood.”

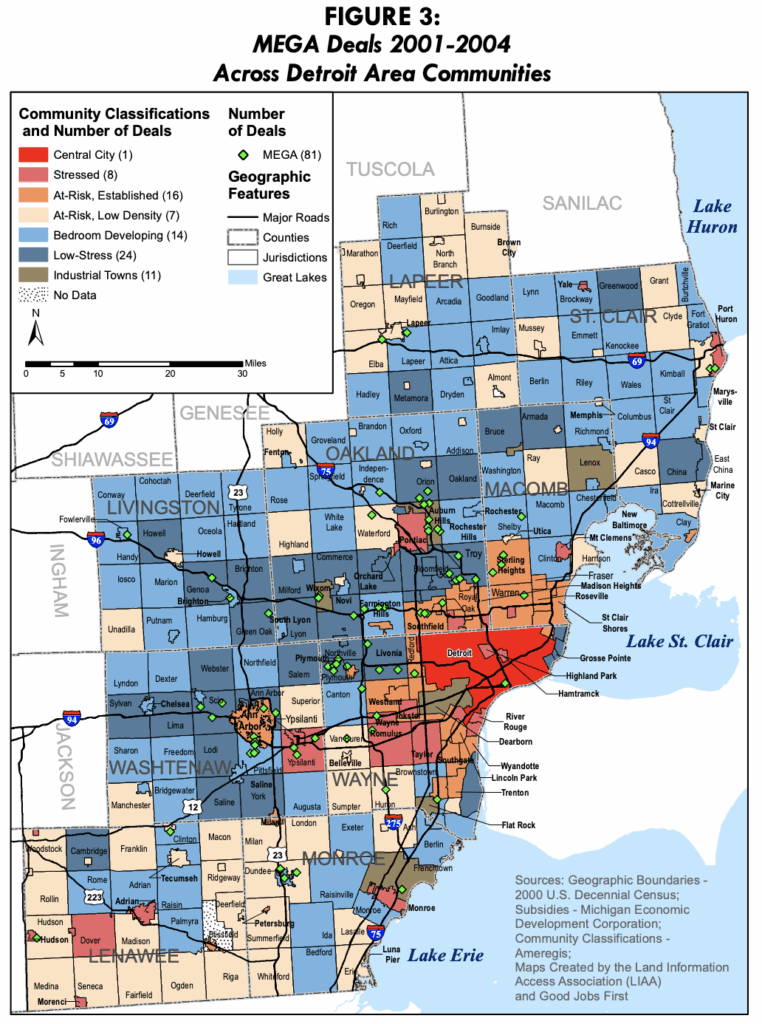

For example, in the Detroit area, we first mapped tax-base wealth. The deepest red (poorest wealth per household) is Detroit; next poorest in orange are inner-ring suburbs. Blue signifies wealth—the deeper the blue, the richer.

Next, we overlaid job losses. Each yellow dot represents a major business closure or mass layoff as officially notified under the 60-day federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act. The 2001–2004 job losses were very heavily concentrated in Detroit and its inner-ring suburbs.

In a facing map, we showed deals awarded by the state’s then most-generous subsidy program, the Michigan Economic Growth Authority or MEGA. Over the same four years, only one of 81 MEGA awards went to Detroit and zero to its 10 most densely populated suburbs.

Harm to Public Education

Two things are true about property taxes: They are the biggest tax a typical US company pays, and that often makes property tax abatements (exemptions from tax, allegedly for public benefit) the biggest subsidy companies get.

Property taxes remain the largest single source of funding for K–12 public education. Indeed, in 19 states, local property taxes provide more than 30 percent of K–12 budgets.

And these two truisms create a tension between private greed and public need.

Yet for many decades, no one knew how much tax abatements cost schools. That has changed, thanks to an obscure government accounting rule adopted a decade ago: the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures.

In the St. Louis metro area…the central city student body, which is 88 percent of BIPOC, loses $1,634 per capita per year.

This amendment to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires most local governments—including school districts—to report annually how much revenue they lose to tax abatements. (Most often, school districts are passive losers to abatements legally controlled under state law by cities or counties.)

The data this reporting rule created is critical for defenders of public education. Now advocates have the information they need to challenge tax abatement practices that are harming the quality of education children receive.

Another truism, this one from economic development, is, as one 1987 study found, that “the poor pay more.” Given the nation’s racialized inequality, it was long assumed that Black students paid the price for tax abatements as well. But now we know for sure.

Statement 77 took effect in 2017, so we now have seven years of data in many places—and it reveals sharp racial and class discrimination.

In the St. Louis metro area, for example, the central city student body, which is 88 percent BIPOC, loses $1,634 per capita per year. That is 91 times the $18 per student per year lost in the largest (and majority-White) suburban district.

The new data reveals similar discriminatory patterns in Cincinnati. There, students in the central city schools lose $2,394 per year and two majority-BIPOC suburban districts lose more than $1,180 per student per year. No majority-White school district loses more than $380 per student per year, and one loses just $104.

In Kansas City, central city students lose $1,925 per capita per year. Upon learning that, the school board became very vocal in opposition to tax abatements with the city council. As Kansas City Public Schools (KCPS) argued, not only were Kansas City students suffering discriminatory losses compared to majority-White suburban districts, most subsidized projects were located on the White side of Troost Avenue, the city’s historical racial dividing line.

The KCPS superintendent at the time, Mark Bedell, called tax abatements “systemically racist.”

New York State schools lose $1.8 billion per year and a broad coalition there is seeking to shield schools from property tax abatement entirely. Schools in the Empire State are unusually dependent on property taxes—they provide more than half of K–12 funding. Yet abatement decisions are made by unelected Industrial Development Agencies in each state, not elected city councils.

There is a bigger national story here as well. School boards lack the power in most states to protect themselves from city and county tax abatements. Why schools are so politically subordinate is a fact whose back story we have yet to uncover. But that structural vulnerability mostly harms BIPOC children: Public school enrollment as of 2022 was already 55 percent non-White, and given demographic trends, that share will continue to rise.

The Network for Public Education points out the racially disparate impacts of attacks on public schools, including vouchers. Scholars, including Josh Cowen, author of The Privateers: How Billionaires Created a Culture War and Sold School Vouchers, trace attacks on public school funding to White supremacist resistance to the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision.

With federal austerity ushered in through President Donald Trump’s budget bill, the harm to public services caused by tax abatements will only become more glaring.

Deregulation of “Anti-Poverty” Incentives

The history of US place-based economic development incentive programs is a cynical bait and switch.

Geographically targeted incentives, such as enterprise zones and tax increment financing (TIF) districts, were enacted by states starting in the 1950s with anti-poverty intent language. Indeed, some of those first laws echoed verbatim anti-slum and blight ordinances from the Progressive Era.

However, over time, those good intentions were subverted. Narrowly targeted subsidies that were effectively restricted to a small number of truly distressed areas were deregulated. More zones and gerrymandered districts were allowed. Eligibility rules were relaxed—sometimes effectively eliminated. Requirements that an area be officially deemed “blighted” became meaningless, as state court rulings allowed localities to make up their own definitions.

TIFs, especially, became associated with suburban sprawl—subsidizing big-box retail that sucked jobs and sales tax revenue away from central cities and older suburbs.

The East-West Gateway Council of Governments, the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the St. Louis metro area, issued a devastating analysis of how $2 billion in TIF funds to retail had subsidized the hollowing out of the region.

The red dots indicate a retail closure, and black dots show a retail opening, between 1998 and 2007.

The study officially found that:

The use of tax incentives has exacerbated economic and racial disparity in the St. Louis region. Historically, tax incentives to private developers are less often used in economically disadvantaged areas and their more frequent use in higher-income communities gives those jurisdictions what amounts to an unneeded, extra advantage.

Virginia’s TIF law says a locality may create a TIF district anywhere it “will promote commerce and prosperity.” Iowa has more than 3,300 TIF districts, including market-rate housing in golf course communities. Illinois bowed to demands from Sears to deregulate its TIF law in 1989, so that the retail chain’s headquarters could flee its iconic tower in Chicago’s Loop (with a racially diverse commuting shed) for a transit-free (and very White) greenfield 29 miles away. That deregulation has plagued the state with excessive “TIF-ing” ever since.

Bias Against Small Business

Large corporations have lobbyists, lawyers, and accountants to help win lower taxes. Given that economic development subsidies effectively amount to corporate tax avoidance, it’s not surprising that small businesses get shortchanged. That disfavors business owners of Black, Latine, Native and Asian communities, who are a rising share of startup founders.

Given the well-documented structural barriers non-White entrepreneurs face—especially less access to outside financing—one would think that an “incentive” to address such a “market imperfection” would be just the remedy. However, by three forms of analysis, state and local spending called “economic development” is making things worse.

On corporate income tax incentives, the biggest prize for corporate lobbyists has been the enactment of the “single sales factor.” This is a change from how states have traditionally required multi-state companies to divvy up or “apportion” their taxable income by state. The net effect has been a huge tax-cut windfall for large manufacturing companies—with no strings attached and no disclosure of costs or benefits.

Illinois, for example, enacted a single sales factor in 1998, even though its comptroller estimated that while 7,014 companies would collectively see their annual tax bills fall by $217 million, just five of them would get almost 28 percent of that amount. State privacy laws forbid the state from specifying the company names in its reporting, but beneficiaries are likely multinational manufacturers, such as Archer Daniels Midland, John Deere, Caterpillar, Motorola, and Amoco.

In 2022, eight megacorporations…received individual-factory megadeals worth an average of $2 billion each, by far a record.

For small businesses selling to local markets within the state—where non-White entrepreneurs are concentrated—the Illinois rule change did nothing. Most of the nation’s largest industrial states have enacted this big-business windfall.

At the company-specific level, we can drill down further. In 14 states, we looked at subsidy programs that are facially open to businesses of all sizes. But sorting more than 4,200 individual deals, we found that large companies (such as publicly traded, multi-state, multinational companies) got 70 percent of the deals and 90 percent of the dollars.

Finally, we looked at every form of spending by three states. Yet even when including small business technical assistance program dollars (that is, staffing as well as incentives), we found that less than one-fifth of the spending benefited small businesses.

Megadeals: Enriching White Billionaires

“Megadeals” is our term for project-specific awards of more than $100 million in public money. We consider them a measure of corruption or special-interest capture. They are the opposite of equity and fairness.

The taxpayer costs per job of such deals are astronomical: often hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars per job. At such prices, the only certainty is that they massively transfer wealth from taxpayers to shareholders. Given whom they benefit—that is, people who own stocks—they are also an instrument of extractive White privilege.

When Mercedes-Benz got $238 million from Alabama in 1993, it set off a wave of studies and pronouncements about the “economic war among the states.” Today, that deal, even in inflation-adjusted dollars, would be less than a third of recent auto-plant subsidy packages.

In 2022, eight megacorporations—chipmakers Intel and Micron; automakers Rivian, Vinfast, Hyundai, and General Motors; steelmaker Nucor; and battery maker Panasonic—received individual-factory megadeals worth an average of $2 billion each, by far a record. (Those are state plus local dollars only: The microchip and battery factories are each getting billions more in federal subsidies.)

In just the past few years, internet giants Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta have received billions in subsidies to build cloud-computing data centers—two Amazon deals alone got a total of $5 billion—and the rate of subsidization is accelerating. That is because state rules make virtually every project automatically tax-exempt, and the race to dominate artificial intelligence is causing a frenzy of new data center construction.

Outrageously, as federal austerity sets in, 12 states are failing to disclose even their aggregate tax revenue losses to data centers.

The wealth-transfer benefit of these deals is grossly discriminatory: In the United States, stocks and mutual funds comprise 35 percent of White wealth, but only 8 percent of Black wealth, and 14 percent of Latine wealth.

The bottom line: structural racism is endemic to state incentive programs….There are very specific, achievable ways to change those rules.

An Antiracist Incentive Agenda

There are some solutions to these injustices:

- Re-regulate place-based incentive programs so that these truly benefit distressed communities and their residents

- Embrace anti-sprawl land-use policies and require deals in metro areas to be located along transit corridors to ensure equitable access to jobs

- Means-test “corporate welfare”—that is, simply deny subsidies to companies above a certain size

- Fix spending priorities by shifting state development budgets to support small businesses and reinstating the traditional three-factor corporate income tax apportionment formula based on in-state sales, property, and payroll.

- Require companies that get incentives to embrace community benefits such as local affirmative hiring and procurement set-asides for firms that are owned by women or BIPOC communities

- Promote metro-area cooperative incentive agreements among cities in given metro areas, like those in Denver and Dayton, OH, to deter job piracy.

The bottom line: Structural racism is endemic to state incentive programs and state rules that govern local practices. There are very specific, achievable ways to change those rules and programs so that small businesses, BIPOC-owned businesses, and their communities intentionally benefit.

Good Jobs First research analyst Anya Gizis helped tell this story, first assembled in April 2025 for University of Connecticut law professors Richard Pomp and John Brittain’s class on Taxation and Racism.